Adding fertilizers to our soil is not as simple as it seems. Plants use some of it, but unseen microbes metabolize fertilizers into gas, including nitrous oxide, a potent greenhouse gas that contributes to our changing climate. How can we not only understand how current agriculture affects our ecosystems, but also use that knowledge to advance new agricultural technology? Amy Randall-Barber from the BIO5 Institute interviewed Dr. Holly Andrews, a postdoctoral researcher working with both the Greg Barron-Gafford research group and Laura Meredith ecosystem genomics lab at the University of Arizona who is looking to answer both those questions. She received her PhD from the University of California, Riverside. In 2021, she was awarded a National Science Foundation fellowship at the UArizona School of Natural Resources and Environment to work with the Meredith lab and in 2023 was awarded a BIO5 Postdoctoral Fellowship. She started a joint postdoc position across the Barron-Gafford and Meredith labs in August 2023.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

ARB: Before we get started, I’ll ask a couple of fun icebreaker questions not related to research. Can you give us a four-letter word, not a five-letter word, that starts with the letter B?

My original response was going to be ‘Bear’ as in ‘Bear Down, go University of Arizona!’ Since I got these questions ahead of time, I was chatting with my friends and they said, obviously the four-letter word you're supposed to say is ‘BIO5.’ But five is a number, so I'm going with ‘bear’ for ‘Bear Down.’

ARB: Both are solid answers. Next question, what is your favorite Catalyst Café order? For those who don't know, the Catalyst Café is our resident BIO5 Institute café. My personal favorite is the prickly pear lemonade.

I also like the prickly pear lemonade, and all their lemonade and tea combinations. I believe they have a good passion fruit tea, too.

ARB: I was told today to try their pomegranate lemonade!

You graduated from the University of California, Riverside with your PhD. Are you a native Californian or where are you from?

I grew up in central Ohio near the Columbus metropolitan region. I did my bachelor's degree at southwestern Ohio at Miami University, and then did a master's at the University of Michigan.

After experiencing the cold, cold winters in Michigan, I thought, ‘I need to get out of here and go to the southwest.’ That's when I moved to California to start my PhD, and I have not wanted to leave because now I'm in Tucson!

ARB: It’s a little hot here compared to California. What brought you to the University of Arizona?

My background is in ecology, and I'm interested in ecosystem science. There are so many ecosystem facilities, Biosphere 2 for example, around the University of Arizona campus. Early on in my PhD, I decided I wanted to come here next for a postdoc. That's what led me to write an NSF postdoctoral proposal with Laura Meredith, which luckily got funded, and then come here.

ARB: I’ve always been curious about that process. You didn’t know Laura Meredith ahead of time, but you learned about her work during your PhD and decided that is the kind of lab you wanted to work in?

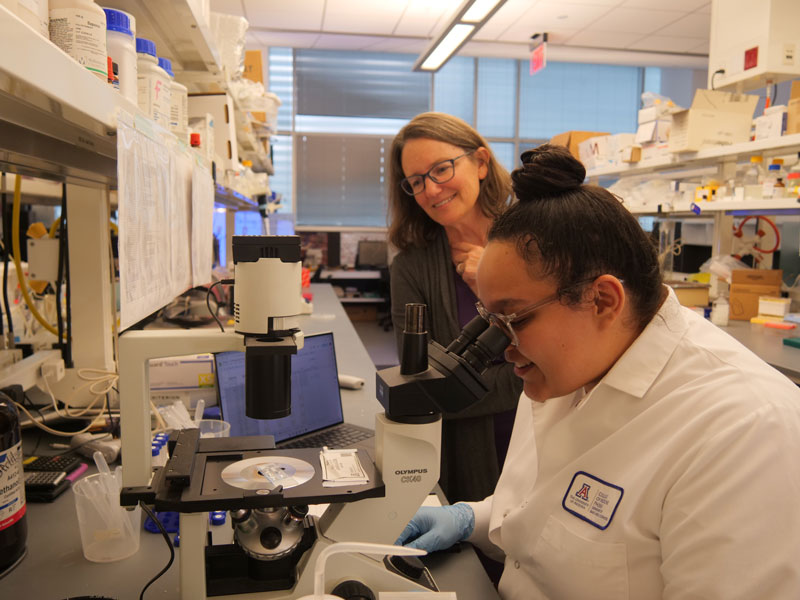

Right. My PhD research looked at gaseous emissions from soils, which is what her lab specializes in. One of my mentors early on in my PhD was Rachel Gallery, another faculty member at the UArizona School of Natural Resources and the Environment. She suggested Laura as a great person to write a proposal with because I wanted to add new skills to my research toolbox.

I ended up cold emailing Laura and saying, ‘Hey, I have this topic I'm interested in, would you like to write this proposal together?’ And she said ‘Yes’. It ended up being a great collaboration, writing the proposal together and then working with her. Since then, I've picked up many new skills that I will carry forward into my career.

ARB: That’s awesome. There’s a whole culture here around ecosystem science. Laura is terrific, she’s worked with us many times.

What first introduced you to the idea of being a researcher – your ‘aha’ moment in your life?

I feel like I stumbled into it, but I've always been interested in wildlife biology from an early age.

My parents are outdoorsy people, especially my dad. They got me involved in local metro parks and volunteer activities. From there, I liked being outside and learning about nature. I was also into music. For a while, I was trying to decide which career path I wanted to take and ultimately landed on biology.

My freshman year of college, I randomly ran into a faculty member who was looking for undergrads to work in his lab. And it snowballed from there.

My ‘aha’ moment would be during my junior year of my undergraduate degree. I applied for a fellowship with the EPA, because I was interested in government research and environmental protection. Unfortunately, it's a program that was cut in recent years from the EPA budget. But it was a way to get undergrads involved in research through government labs and agencies. I did an internship program with one of the ecology divisions on the east coast in Rhode Island working in wetlands.

It was a great experience because they pushed me to design my own experiment and collect the data. I went through the whole scientific process myself with help from my mentors. I was included in a couple of publications that came out of that work. I think it was that moment where I thought, ‘I can do this.’

I felt valued as a contributor to science, even though I was still at the undergraduate level.

From there, I saw research as a potential career. It was fun to do those experiments and learn more about wetland degradation. We were looking at how wetlands along the east coast are being degraded by climate change, as well as urbanization.

Runoff causes wetlands to lose their resilience that can help counteract hurricanes and other extreme weather events. It was a learning experience to contribute new data and knowledge to this important topic of making sure our ecosystems continue to be sustainable in the face of a changing landscape and climate change.

ARB: That’s very interesting.

You had two fellowships at the same time for about eight months at the University of Arizona and they overlapped. Were the projects for each of the fellowships the same or different?

The projects are tackling two sides of the same research question.

My NSF fellowship tackles agricultural systems and nitrogen cycling in the soil. When we are adding fertilizer to agricultural fields, where does that fertilizer go? We know a small fraction ends up in the plants; we add fertilizers to help the plants grow. But it's not all getting there. Instead, we know that a lot is lost to the atmosphere as greenhouse gases. The number one source of nitrous oxide, a potent greenhouse gas into the atmosphere, is from agricultural soils. That's produced by soil microbial communities, and I want to understand how that happens.

I don't necessarily want to say, ‘can we engineer our soils?’ But can my research inform how we use fertilizer in our agricultural systems to make them more climate-friendly? Can we make sure when farmers spend money on buying fertilizer it gets into plants?

I was doing stable isotope analyses, where we injected isotopically labeled fertilizer into the soil to track that process in the field. We want to see where the fertilizer goes – is it incorporated into microbial biomass, so into DNA itself? How much of it is released as gases? How much of it is getting into plants and how are plants using it once they acquire it?

My BIO5 Postdoctoral Fellowship builds off that by looking at how nitrogen gases move through the soil, and then leave the soil to go into the atmosphere. Without getting too far into the weeds of the nitrogen cycle – it can be complicated to talk about – there are different ways that these gases can diffuse through the soil. Microbes can eat these gases and use them for their own metabolism. We're trying to track how much of these gases microbes consume and produce. Plus, how fast do gases move through the soil? How does that relate with water because we're irrigating soils? If you're adding water, it can slow the diffusion and movement of those gases through the soil.

We are teasing apart the physics of the soil system, rather than the biology and some of the other mechanics of agricultural soils. In a way, both these projects are related to nitrogen metabolism in agriculture and fertilizer use, but from two different methodological approaches.

ARB: You’re from the Midwest area and I know there’s a lot of farming there. Did you stumble into this area of research or is there a relationship with agriculture that led you down this path? Where did that curiosity come from?

It’s funny you asked this question, because I really did not. I was kind of anti-agriculture research when I was first thinking about a direction. I enjoyed working in wild lands, and another reason I moved to the southwest for my PhD was to work in desert systems specifically.

But I keep finding myself working in agriculture, because it's an important problem we need to address in thinking about the future of society. How are we going to feed everyone and how do we feed everyone in a sustainable way?

There are all these interacting pieces related to society, wild lands and ecosystems that you can ask in the context of an agricultural system. And so, I find myself coming back to agriculture.

What I'm finding is that it's more complicated than we think from an ecological perspective. Most people tend to think of agricultural systems as very simplified ecosystems where we are growing one type of crop in one field area. They think there are no interesting questions to ask, but we're finding out that soil is very complex. It's hard to tease apart what's going on in these soils, even though we might think it's a simple question.

ARB: I'm sure these last eight months have been busy keeping up with both projects, but the NSF fellowship has now ended. So now you just have one fellowship that you're working on. Do you see yourself staying at the University of Arizona?

I would love to stay here, and I've been trying to find something more permanent.

I started a new postdoc position, which is split across two labs, in the Barron Gafford lab that is also in agriculture. It’s focusing on agrivoltaics, which is the mixing solar panels and solar energy with agricultural cropping systems and different types of agricultural systems.

The idea is that we bring together our energy and our food in the same land area. There was a report sent out across the university about sustainable agriculture in the future, and agrivoltaics was mentioned as one of those possibilities. This is still very new research. We can ask similar questions in agrivoltaics that we've asked in other agricultural systems, but we might get different answers. What works well in traditional agriculture might not work as well, and we need to think about optimizing the efficiency of that system to be more sustainable. At the same time, we're using less land area to get multiple types of outputs that are useful to society.

I'm excited to move forward and combine my previous work in the Meredith lab and apply those same ideas in an agrivoltaic setting in the Barron Gafford lab. It's been nice to have this split position where I can focus on one common study site but ask different questions at different scales. In the Meredith lab, I've been focusing on tiny spatial scales, looking at what's going on immediately next to the plant in the soil. And in the Barron Gafford lab, we're zooming out to the field level.

ARB: What does voltaic mean?

Voltaic is shorthand for anything that produces voltage, which in this case would be solar panels. If you split the word “agrivoltaic,” there's the “agri,” which is agriculture, and the “voltaic” part which is solar panels. This word was generated from the idea that we're putting both of these on the same parcel of land.

ARB: What is your overall personal research goal? Where do you want to see yourself in your research?

I've been interested in research for a long time, and I want to keep doing it as part of my career. I want to combine research with some kind of educational perspective. When I talk about this, I want to be either in a traditional educational setting, like in an academic institution, or in a government setting that has a substantial outreach program associated with it.

I think public education outside of academic institutions is equally as important. It connects us with broader policies that we're trying to change and broader thinking about sustainable systems. It’s important that everybody is on the same page about how we can potentially move forward.

ARB: Have you had any influential mentors in your life, either personally or educationally?

I would say all my academic advisors across undergraduate and graduate school.

If I'm calling out specific names, I’d have to say my first mentor that I had in research, which was Beth Watson. She was the postdoc that was involved in the project at my EPA fellowship in Rhode Island. She was very inclusive and put me as a co-author on all her papers. I felt valued as a researcher by working with her. It connects with my ‘aha’ moment when I realized I can do research for a career. She was the one that started that process.

Now, she’s faculty at Drexel University in Pennsylvania. We’ve kept in touch, especially during my PhD when I was doing remote sensing work with drones and flying drones to look at different aspects of ecosystem vegetation. She was doing the same thing in Pennsylvania, and we would email back and forth to talk about it. It was completely different from what we did together in Rhode Island. It's been great to keep in touch with her and she's been so supportive of my whole research career. I needed that when I was going through college. It was nice having women mentors in STEM because it was important for seeing myself in research.

ARB: What’s next for you? Anything else you’d like to share about your future aspirations?

I just started this new postdoc position, so I'll be sticking around at the University of Arizona for at least another year, potentially longer.

I've been exploring options in the educational academic sector as well as the government, especially the USDA and USGS that are environmentally and agriculturally focused agencies. At this point, I’m trying to figure out where I’m going to land while continuing research on agriculture; combining energy, food and natural ecosystems and what ecosystem sustainability looks like in the long term.

ARB: Thank you – I have a feeling one of these days we’re going to see your name on something awesome that you’ve discovered to help the future of humans on this planet.